Darn Close to a Perfect Story

"Show, don't tell": writers are dogged by this one, as I noted in an earlier post, and not only because showing rather than telling is critical to the creation of a good story, but also because it's so hard to do. We all want to fall back on the crutch of explaining things, which is both easy and somehow comforting. I'm reminded of a simple and beautifully played gesture by Robert Duvall in his role as an over-the-hill newspaper editor in The Paper: he's a heavy smoker, and we've already seen him hacking, but in passing he makes a point of gently patting his lighter and pack of cigarettes where they sit beside him on the desk--just making sure the fix is still handy when he needs it.

There are a lot of really good books out there that challenge writers' addiction to telling and explaining too much: not only Robert McKee's Story, noted earlier, but Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Renni Browne and David King. (This one is famous for the helpful acronym RUE--Resist the Urge to Explain. Romance writer Kathleen Nance has a good, quick discussion of this and related topics on her Web page.) As good as those books are, though, it stands to reason--given the subject at hand--that the best possible guide would be, not a work of nonfiction that tells us not to tell, but a work of fiction that shows us how to show.

For this I can find no more nearly perfect example than "The Swimmer," a short story by John

Cheever published in the New Yorker in 1964 and four years later released as a motion picture starring Burt Lancaster and directed by Frank Perry and Sydney Pollack. I read the story when I was about eighteen or so, and, having just finished watching the film now nearly twenty-three years later, I wonder just what I really understood of Cheever's tale back then. This is a story for grown-ups if there ever was one, and yet I saw something there that has stayed with me all these years.

Cheever published in the New Yorker in 1964 and four years later released as a motion picture starring Burt Lancaster and directed by Frank Perry and Sydney Pollack. I read the story when I was about eighteen or so, and, having just finished watching the film now nearly twenty-three years later, I wonder just what I really understood of Cheever's tale back then. This is a story for grown-ups if there ever was one, and yet I saw something there that has stayed with me all these years.I first became attracted to Cheever's work when I was fresh out of Basic Training at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and any contact with the outside world seemed an enormous privilege. I happened to pick up a copy of Time magazine containing his obituary, and something the reporter said--about a world of neatly trimmed suburban lawns and glasses of gin and tonic over shaved ice--immediately hooked me. As a southerner, I've tended to feel an antipathy toward the fact that the preponderance of American fiction centers on the northeastern part of the nation. That's where most American writers come from, of course, but I'll confess to having been left cold by many a prep-school tale or yet another story of a middle-aged northeastern suburbanite confronting his mortality/sexuality/blah-blah-blah-ality. And on the surface, "The Swimmer" is just another entrant on that long gray line. But it's not: this is literature in the greatest of traditions, harkening back to James Joyce and Huckleberry Finn, to Dante and Odysseus--all the way back to Genesis and the Gilgamesh.

Overblown comparisons? I don't think so; after all, "The Swimmer"--the story of one man's quixotic quest to swim across his neighborhood, from pool to pool--is, though some might call it a mock epic, an epic in the more true sense. As with Joyce's Ulysses, the fact that the stakes are deceptively trivial should not prevent the discerning reader/viewer from understanding that what we are witnessing here is hardly less than a literal life and death struggle. If it's an epic, then that makes Ned Merrill, our titular athlete/explorer, a hero. Many would call him an antihero, but I think you'd have to have a pretty hard heart not to root for Neddy all the way--even when you find out some things I'm not going to reveal here.

I haven't gone back and read the story in all these years, but can only imagine how powerful it would be now if it has stayed with me all this time. (This doesn't always work, of course: when I was thirteen, I thought Jack London's Martin Eden was a masterpiece, but only a few years later I made the mistake of reading it again and realized it was little more than whiny drivel--specifically, whiny tough-guy drivel.) But seeing the movie at forty-one gave me an entirely different appreciation for what Ned confronts--those very real terrors that we all know, the ones far more frightening than giant anacondas or serial killers in hockey masks. On that basis, I'd say this is the scariest film I've seen other than Glengarry Glen Ross. Imagine if Twilight Zone had been on HBO (which of course didn't exist back then, but which would have allowed Rod Serling much greater creative elbow room), and that's The Swimmer.

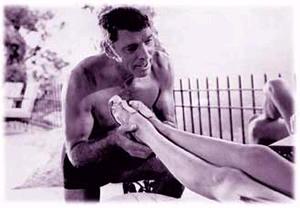

I haven't gone back and read the story in all these years, but can only imagine how powerful it would be now if it has stayed with me all this time. (This doesn't always work, of course: when I was thirteen, I thought Jack London's Martin Eden was a masterpiece, but only a few years later I made the mistake of reading it again and realized it was little more than whiny drivel--specifically, whiny tough-guy drivel.) But seeing the movie at forty-one gave me an entirely different appreciation for what Ned confronts--those very real terrors that we all know, the ones far more frightening than giant anacondas or serial killers in hockey masks. On that basis, I'd say this is the scariest film I've seen other than Glengarry Glen Ross. Imagine if Twilight Zone had been on HBO (which of course didn't exist back then, but which would have allowed Rod Serling much greater creative elbow room), and that's The Swimmer.A few caveats. Because the movie was made in 1968, it has more than a few of the cheesy gimmicks to which filmmakers of that time were given: dreamy dissolves, a little bit of heavy-handed imagery here and there, and a score by Marvin Hamlisch that, while beautiful, ventures into the realm of the lachrymose. Some of the supporting actors are a bit wooden, and you do have to put up with about three minutes of a very young Joan Rivers, who admittedly does a good job with her role. But the ladies (and some of the men) won't mind watching Burt Lancaster run around in a Speedo all movie long. The guy was fifty-five at the time, believe it or not, and in an era long before working out was a standard habit, he still looked good enough to walk around barely dressed--and in one scene, daring for the time, almost entirely undressed.

It's no mistake, of course, that Neddy Merrill is all but naked for the entire film, which takes place virtually in real time. (Incidentally, it was a box-office flop, because audiences at the time weren't ready for something like this.) But I've already said more than enough here, and anyway my point was

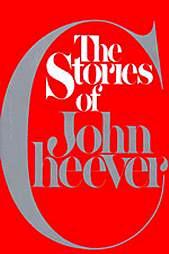

It's no mistake, of course, that Neddy Merrill is all but naked for the entire film, which takes place virtually in real time. (Incidentally, it was a box-office flop, because audiences at the time weren't ready for something like this.) But I've already said more than enough here, and anyway my point was that this tale--both the short story and the movie--is a classic illustration of showing rather than telling. If you're a writer, watch the film, and next time you're working on something and you have an urge to explain a bunch of backstory, remember The Swimmer: had Cheever (shown left) not doggedly resisted the urge to explain, cutting down what was originally a novella of some 150 pages, he literally would have had no story at all. If he'd chosen to introduce us to Ned, emerging from that first swimming pool to the offer of a gin and tonic with a twist of lemon, in such a way that we already knew everything about him, then there would have been no point in going on. Click on the image (right side) for a link to this book.

that this tale--both the short story and the movie--is a classic illustration of showing rather than telling. If you're a writer, watch the film, and next time you're working on something and you have an urge to explain a bunch of backstory, remember The Swimmer: had Cheever (shown left) not doggedly resisted the urge to explain, cutting down what was originally a novella of some 150 pages, he literally would have had no story at all. If he'd chosen to introduce us to Ned, emerging from that first swimming pool to the offer of a gin and tonic with a twist of lemon, in such a way that we already knew everything about him, then there would have been no point in going on. Click on the image (right side) for a link to this book.

Producers and consumers of rock were mostly young kids from privileged or relatively privileged backgrounds, the beneficiaries of an unprecented prosperity that made possible for the first time in history the opening up of university doors to a solid plurality--if not a majority--of the youth population.

Producers and consumers of rock were mostly young kids from privileged or relatively privileged backgrounds, the beneficiaries of an unprecented prosperity that made possible for the first time in history the opening up of university doors to a solid plurality--if not a majority--of the youth population.

It's hard to see it afresh now, because that sort of plot has been done so many times since then--and usually quite poorly, as in the two sequels--but when it came out, that movie was one of the freshest, most original things I'd ever seen. There's not an ounce of fat on that script, which is as close to perfection as just about any piece of writing I've ever encountered.

It's hard to see it afresh now, because that sort of plot has been done so many times since then--and usually quite poorly, as in the two sequels--but when it came out, that movie was one of the freshest, most original things I'd ever seen. There's not an ounce of fat on that script, which is as close to perfection as just about any piece of writing I've ever encountered.