Sweetheart of the Rodeo; or, When the Country Rocked and Raged

Recently I've rediscovered the music of The Flying Burrito Brothers, a little-known but highly influential band formed by Gram Parsons after he left the Byrds in 1968. Parsons, more than any other figure in music, was responsible for the rise of country-rock in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and with it the growth of the singer-songwriter movement in the years that followed. This

Recently I've rediscovered the music of The Flying Burrito Brothers, a little-known but highly influential band formed by Gram Parsons after he left the Byrds in 1968. Parsons, more than any other figure in music, was responsible for the rise of country-rock in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and with it the growth of the singer-songwriter movement in the years that followed. This  move in turn helped bring about the blurring between country and rock that we see today, but it wasn't always that way.

move in turn helped bring about the blurring between country and rock that we see today, but it wasn't always that way.Back in the day, country and rock didn't just symbolize two different tastes, but two whole different worlds. Never mind that rock 'n roll owes almost as much to country as it does to R 'n B--in fact, it's not too much of a stretch to say that the entire medium emerged from an amalgam of the various styles employed by poor blacks and poor whites in the southern United States during the first half of the twentieth century. But whereas the rockers of the 1960s saw themselves as philosophically aligned with the music of Detroit (despite the fact that that music was far more unabashedly commercial), they could not have been more removed from Nashville.

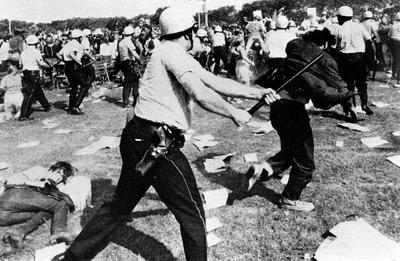

People think our nation is divided now, but we have only to look at other eras--a certain conflict in the 1860s, for instance--to put today's mood into a proper context. The divisions of the 1960s were arguably as strong, leading as they did to outbursts of violence that, while mild compared to the passions that raged in the years leading up to and including the Civil War era, were far beyond anything we're experiencing now. Perhaps it's in the nature of America to be divided, because we're a nation founded on the principle of individual thought, but that's another discussion.

People think our nation is divided now, but we have only to look at other eras--a certain conflict in the 1860s, for instance--to put today's mood into a proper context. The divisions of the 1960s were arguably as strong, leading as they did to outbursts of violence that, while mild compared to the passions that raged in the years leading up to and including the Civil War era, were far beyond anything we're experiencing now. Perhaps it's in the nature of America to be divided, because we're a nation founded on the principle of individual thought, but that's another discussion.

What's important here is the cultural importance of the marriage between country and rock, an idea we take for granted today, but one that seemed truly revolutionary (or counterrevolutionary, depending on who was talking) four decades ago. Rock 'n roll was the music of hippies, anarchists, communists, practitioners of free love and experimenters with substances virtually unknown to the wider culture only a few years before.

Producers and consumers of rock were mostly young kids from privileged or relatively privileged backgrounds, the beneficiaries of an unprecented prosperity that made possible for the first time in history the opening up of university doors to a solid plurality--if not a majority--of the youth population.

Producers and consumers of rock were mostly young kids from privileged or relatively privileged backgrounds, the beneficiaries of an unprecented prosperity that made possible for the first time in history the opening up of university doors to a solid plurality--if not a majority--of the youth population.Country, on the other hand, was--to an even greater extent than today--the music of the workin' man, the salt of the earth. It represented a world of people who believed in God and the flag, who relied more on common sense than education, a segment of the nation (far larger than the hippies, by the way) who had nothing but disdain for everything the hippies represented. Therein lay a great irony, in that hippie revolutionaries claimed to speak for the proletariat, yet the proletariat by and large wanted nothing to do with them.

When President Nixon spoke of the "Silent Majority"--the hardworking, conservative populace that believed in a strong military, law and order, and a host of ideas antithetical to those coming out of Greenwich Village, Harvard Yard, Haight-Asbury, and Hollywood--these were the people he meant. True, many of them were, in musical terms, truly silent, because most represented a generation for which music had nothing like the kind of power it possessed for those of us born after World War II, but if the Silent Majority had a sound, it was that of the acoustic guitar, the standup bass, and the dulcimer. Theirs was an ethic embodied in the words of Merle Haggard's smash 1969 country hit, "Okie from Muskogee":

When President Nixon spoke of the "Silent Majority"--the hardworking, conservative populace that believed in a strong military, law and order, and a host of ideas antithetical to those coming out of Greenwich Village, Harvard Yard, Haight-Asbury, and Hollywood--these were the people he meant. True, many of them were, in musical terms, truly silent, because most represented a generation for which music had nothing like the kind of power it possessed for those of us born after World War II, but if the Silent Majority had a sound, it was that of the acoustic guitar, the standup bass, and the dulcimer. Theirs was an ethic embodied in the words of Merle Haggard's smash 1969 country hit, "Okie from Muskogee":We don't make a party out of lovin'

We like holdin' hands and pitchin' woo

We don't let our hair grow long and shaggy,

Like the hippies out in San Francisco do.

The song is a scathing dismissal of the hippie lifestyle and all its facets--not just free love and long hair, but drugs, anarchism, opposition to the military--all the behaviors glorified in rock 'n roll but despised by the denizens of Nashville and their cohorts around the nation.

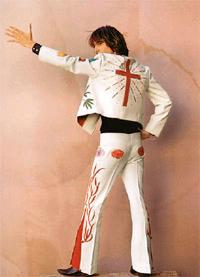

Hence the boldness of the statement made by Parsons, whose

International Submarine Band (1965-67) first introduced the idea of country rock. That idea gained far greater exposure after he joined the Byrds, who had already been moving in that direction but whose 1968 album Sweetheart of the Rodeo served to introduce country rock to the world. And the introduction was not well received: David Fricke, in the liner notes to a 1997 reissue of Sweetheart, called it "career suicide" for the Byrds.

International Submarine Band (1965-67) first introduced the idea of country rock. That idea gained far greater exposure after he joined the Byrds, who had already been moving in that direction but whose 1968 album Sweetheart of the Rodeo served to introduce country rock to the world. And the introduction was not well received: David Fricke, in the liner notes to a 1997 reissue of Sweetheart, called it "career suicide" for the Byrds.Though some of the songs on this album (most were covers) fit in with the zeitgeist--for

example, Woody Guthrie's "Pretty Boy Floyd," well-timed for an era when outlaws had newly reemerged as heroes thanks in large part to the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde--one can only imagine what progressives made of the group's unironic cover of "The Christian Life" by Ira and Charlie Louvin. The very fact that the album consists almost entirely of covers is a reflection of Columbia Records' hesitatancy about the career move: the label forced the group to pack in a great deal of more typical Byrds material, and left out several original Parsons compositions later included on the reissue. As for the reaction of the country world, this too isn't hard to imagine: later, when Parsons--setting out on a solo career when he left the Flying Burrito Brothers--sought to work with Haggard, the latter dismissed him as an acid-head who didn't understand country.

example, Woody Guthrie's "Pretty Boy Floyd," well-timed for an era when outlaws had newly reemerged as heroes thanks in large part to the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde--one can only imagine what progressives made of the group's unironic cover of "The Christian Life" by Ira and Charlie Louvin. The very fact that the album consists almost entirely of covers is a reflection of Columbia Records' hesitatancy about the career move: the label forced the group to pack in a great deal of more typical Byrds material, and left out several original Parsons compositions later included on the reissue. As for the reaction of the country world, this too isn't hard to imagine: later, when Parsons--setting out on a solo career when he left the Flying Burrito Brothers--sought to work with Haggard, the latter dismissed him as an acid-head who didn't understand country.Acid-head he may have been--Parsons lived fast and died young in 1973 at a mere twenty-six years of age--but there's no denying that Gram Parsons was a visionary and a great interpreter of American folk idioms. The very fact that his achievement doesn't immediately seem so remarkable today is the greatest evidence of his ideas' triumph.

3 Comments:

Hmmm, sounds like change will always be like pulling teeth, as the saying goes. Resist, gripe and divert until such time as one realizes after the tooth is finally pulled, that it was actually a Great idea and in retrospect, glad it happened.

I think our country benefitted by the refreshing musical wind.

Of course...in 20 years..I'll be curious if that enthusiasm will also embrace Rap.

I think that sometimes about rap--in fact, I was thinking this just the other day, when I happened to be listening to some really solid, old-school rap/hip-hop, namely The Low End Theory by A Tribe Called Quest (1991). It's so strong musically (real instruments--real jazz musicians), and imbued with such lyrical richness and humor, that I think almost any rock fan (if not a pop fan) could come to appreciate it pretty quickly.

But that's not the case with a lot of the more recent stuff, especially almost anything identified as "So and So featuring Somebody Else" (e.g., that really noisy and repetitive song from the summer of 2004 that featured Usher and a bunch of others.) Most of this is pretty mechanical and, though usually filled to the brim with an over-the-top sexuality, lifeless at heart. Noisy, uninteresting musically, dependant on a lot of posing and a video that looks like about ten thousand others--yeah, I wonder about the lasting power of most rap and hip hop myself. But I do believe that 20 years from now, people will still appreciate Tribe, Public Enemy, and a handful of others, including the always fun, friendly, and fresh Salt 'n Pepa.

Ah!

Time will separate the Chaff of Rap from the Rappin' Wheat!!!!

Got it.

Post a Comment

<< Home